https://gds.blog.gov.uk/story-2011/

A GDS Story 2011

This is one part of “A GDS story”. Please read the introduction and the blog post that explains this project.

More of the story: 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021

January

The first members of the alpha team assembled in Hercules House, a government building near Waterloo station: Tom Loosemore, Richard Pope, David Mann and Jamie Arnold.

February

From February onwards, more team members joined: James Stewart, James Weiner, Paul Annett, Relly Annett-Baker, Lisa Scott, Ben Griffiths, Matt Patterson, Joshua Marshall, Helen Lippell, Russell Garner and Peter Jordan.

March

Work began on the alpha. Tom Loosemore briefed the team: "We're making something that will make ministers sit up and say 'I want one of those'."

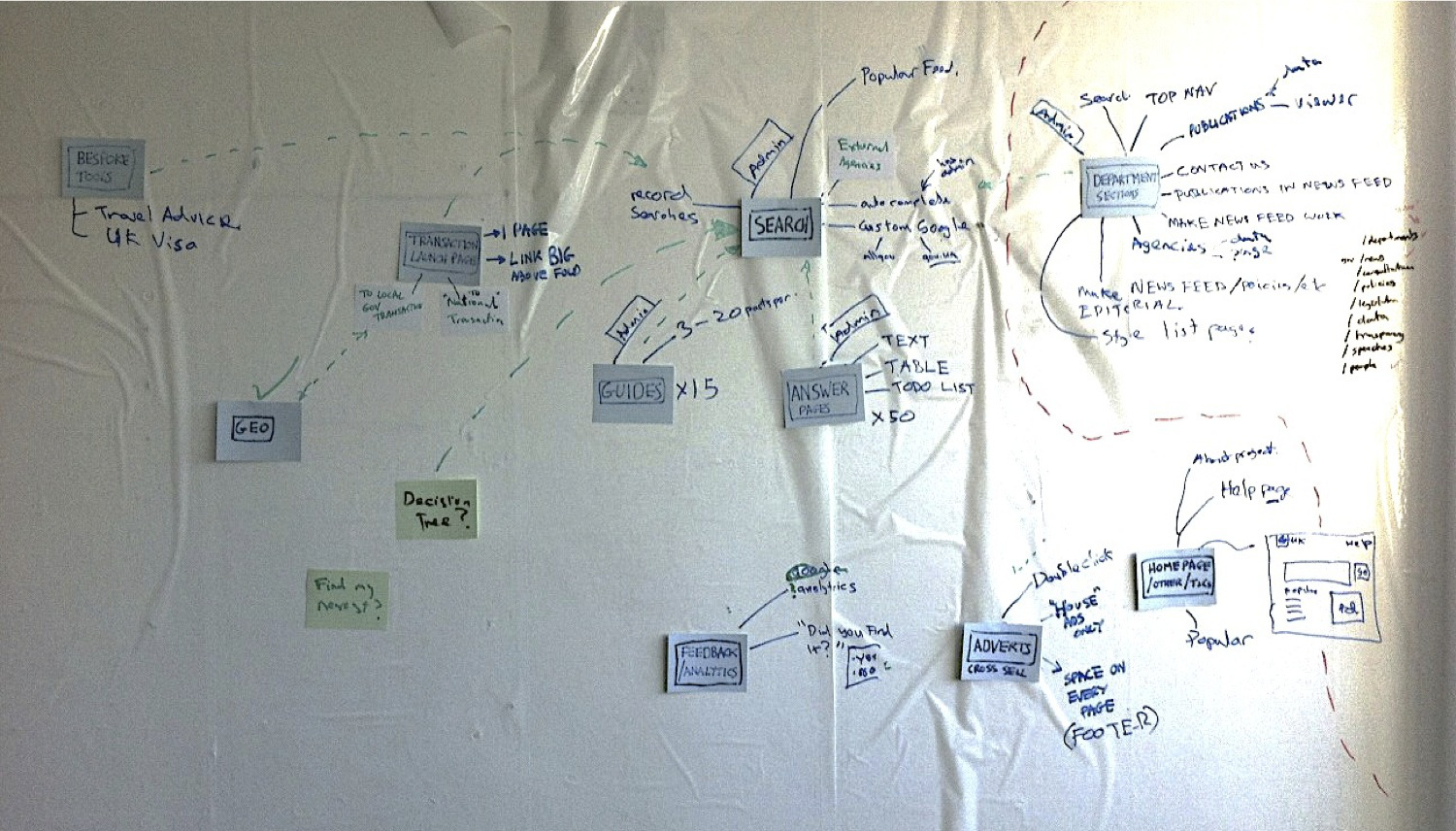

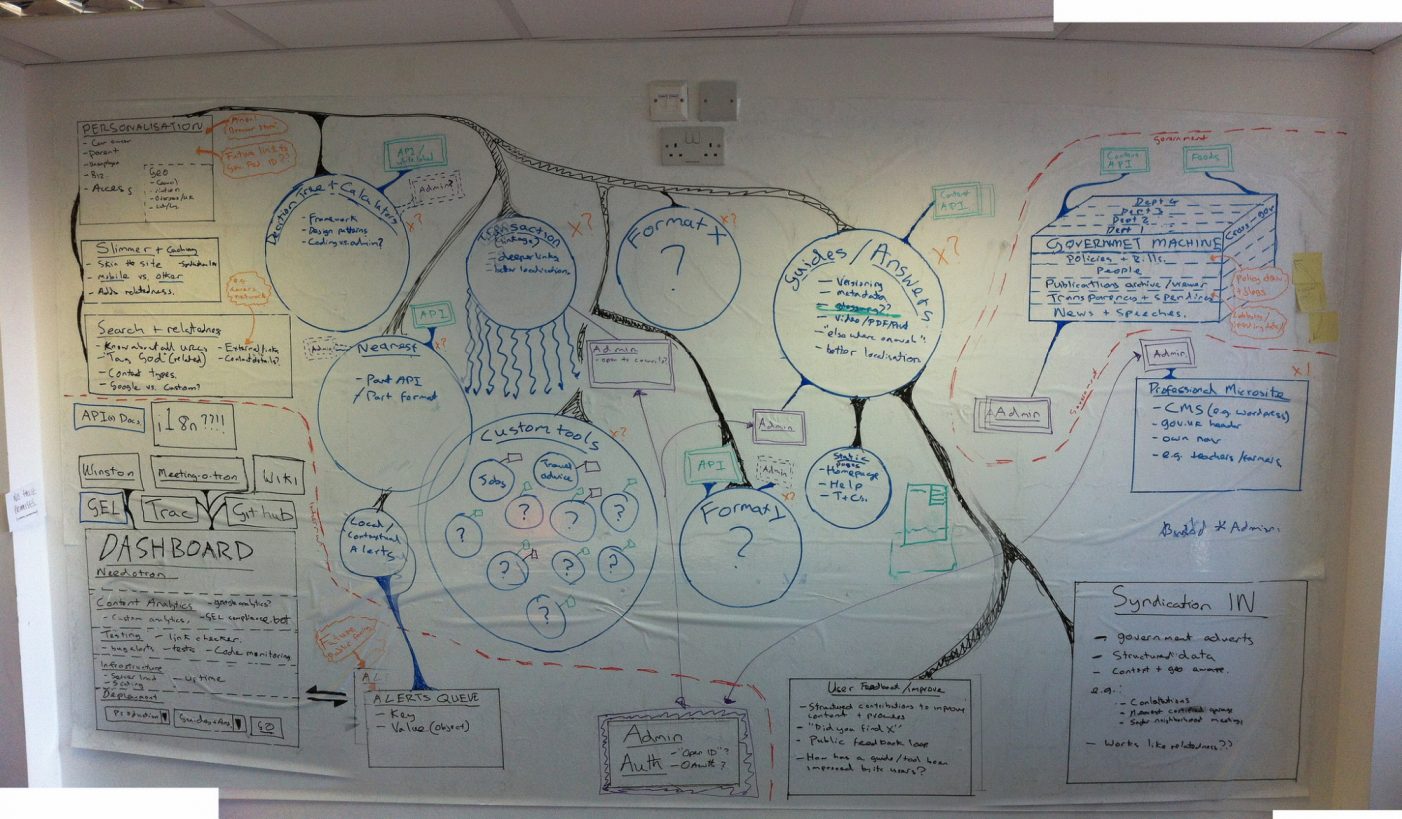

The team drew a mental map of the project on a wall.

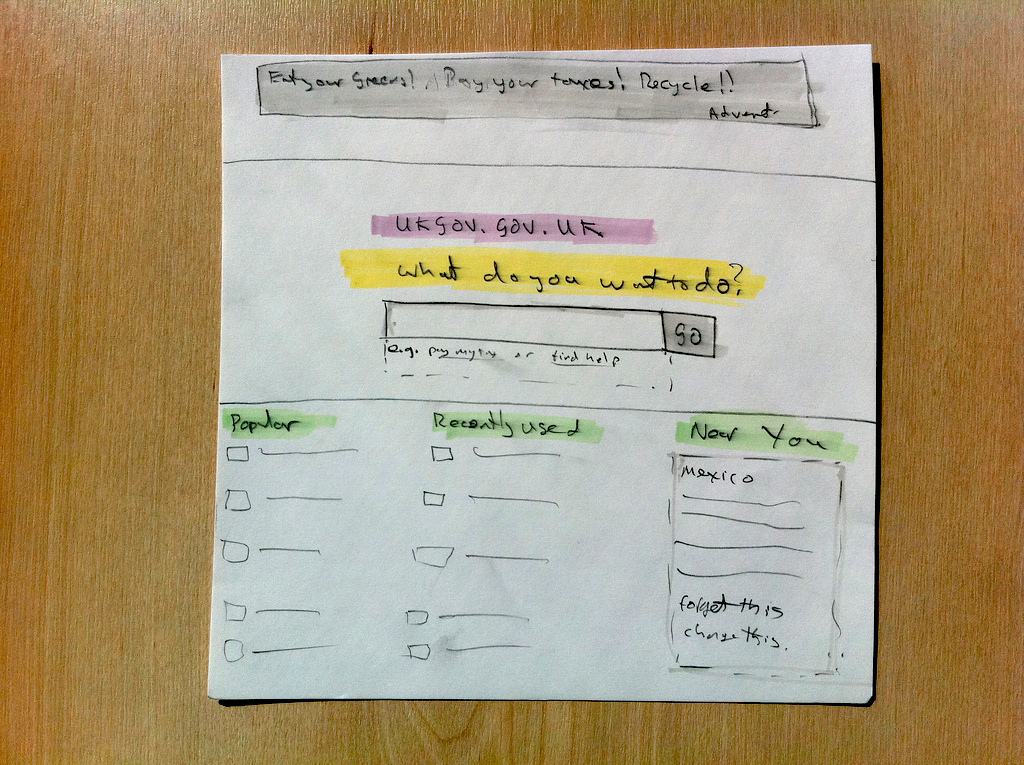

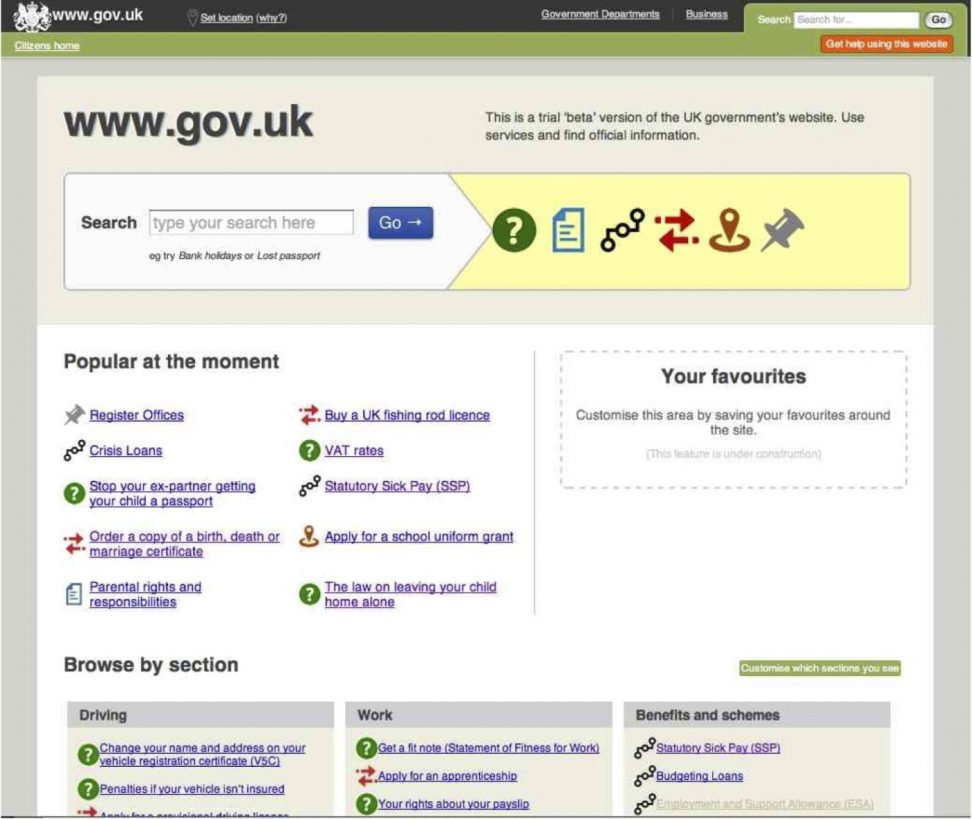

This early sketch by Richard Pope shows how different the team's ideas were from what followed later (and also, how different they were from Directgov). This sketch assumed that there would be space for a banner advert-shaped call to action at the top of the page. The page was dominated by a central search box and the huge headline "What do you want to do?" And the name, at this stage, was assumed to be “ukgov.gov.uk”.

Richard posted hundreds of other sketches on Flickr.

Photo: Richard Pope

After a few weeks of ideas and prototypes, the team realised they were being far too ambitious, and that their initial approach wasn’t the right one. Richard Pope insisted: “We have to do this properly.” They needed to put user needs first, and prioritise them, so decided to narrow the focus of the alpha on the top 100 user needs. These were written on cards and sorted into categories on the wall.

15 March

The first public mention of the Government Digital Service, “a new organisation merging Directgov and a number of other smaller teams”.

29 March

The alphagov project was publicly announced, with Tom Loosemore in charge (helped by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office's then head of digital, Jimmy Leach). A candid blog post declared:

Normally an 'alpha' would not be made public. You normally open the doors at a later, 'beta', phase in a site's development. In this instance, we think it's vital to get real feedback from users on what is a relatively radical product approach.

April

Five sprints (weeks) in, and the alpha team were struggling with the workload and lack of people. Much later, after the alpha was public, Jamie Arnold wrote about the problems:

We (or rather I) didn't get everything right. By the end of sprint 5 I was just about ready to hang up my Excel and opt for a life at the RSPCA.

Once the team was fully assembled, they published a list of team members.

7 April

This was the first public glimpse of the alpha, in a brief report in The Daily Telegraph.

28 April

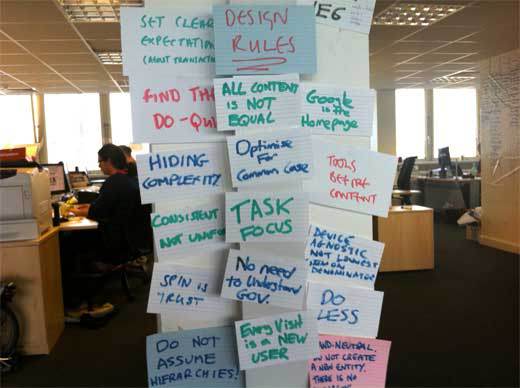

Richard Pope wrote a blog post about the first design rules, including "Do less", "Find the quick do", and "Consistent, not uniform". These would later form the basis for the Design Principles.

9 May

David Mann, a member of the alpha team, wrote about digital projects across government, pointing out (not for the last time) that GDS was not the first to tread this path:

We see our project as part of a wider cultural movement with many advocates across government, seeking far more agile, iterative, user-need-driven digital product development.

11 May

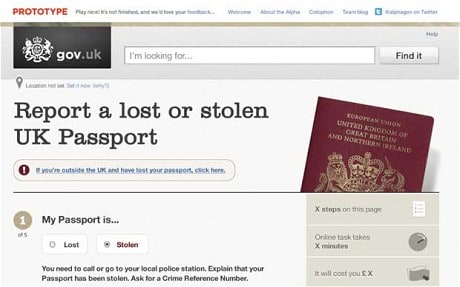

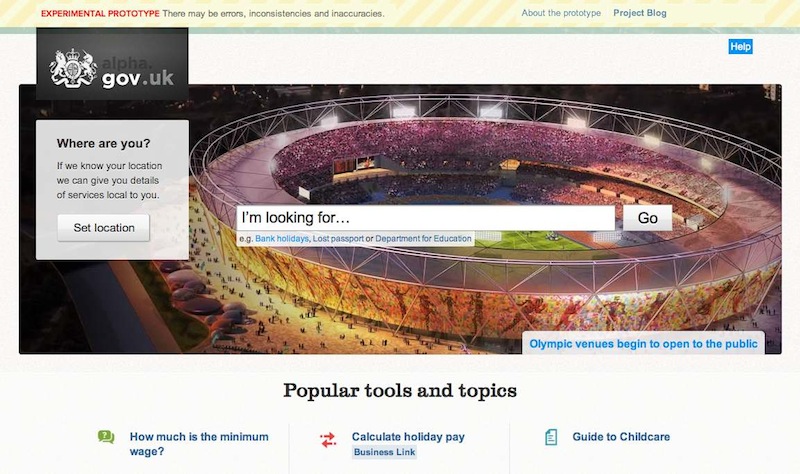

Launch day for the alpha (one day later than planned).

The Olympic stadium picture was added late. The team were told to give the site "a West Coast look". The goal was to create something that looked radically different than other government websites at the time.

The reception was generally very positive, but there were some critical voices. Leisa Reichelt (who would later join GDS and become its Head of User Research), criticised the alpha team for (among other things) not hiring a user experience lead:

Unfortunately, as a User Experience practitioner, I feel kind of glum. This project has talked the talk of caring about the end user, of placing their needs at the centre of the project and above the needs and desires of government, but at every step, they’ve done little to set a good example for how others should actually do this.

Tom Loosemore wrote up his thoughts a few weeks later:

The prototype was developed in 12 weeks for £261,000... A boundary-pushing experimental prototype (aka a Minimum Viable Product) was delivered by an in-house team working in an open, agile way, placing user needs at the core of design process. This isn't a new approach, but it's one that still all too rare across government.

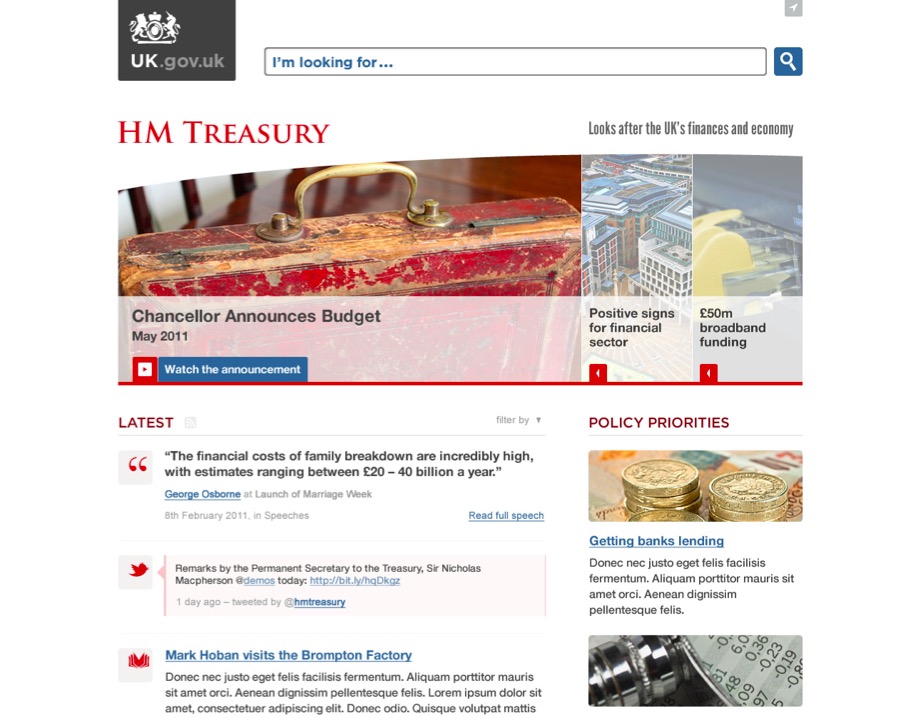

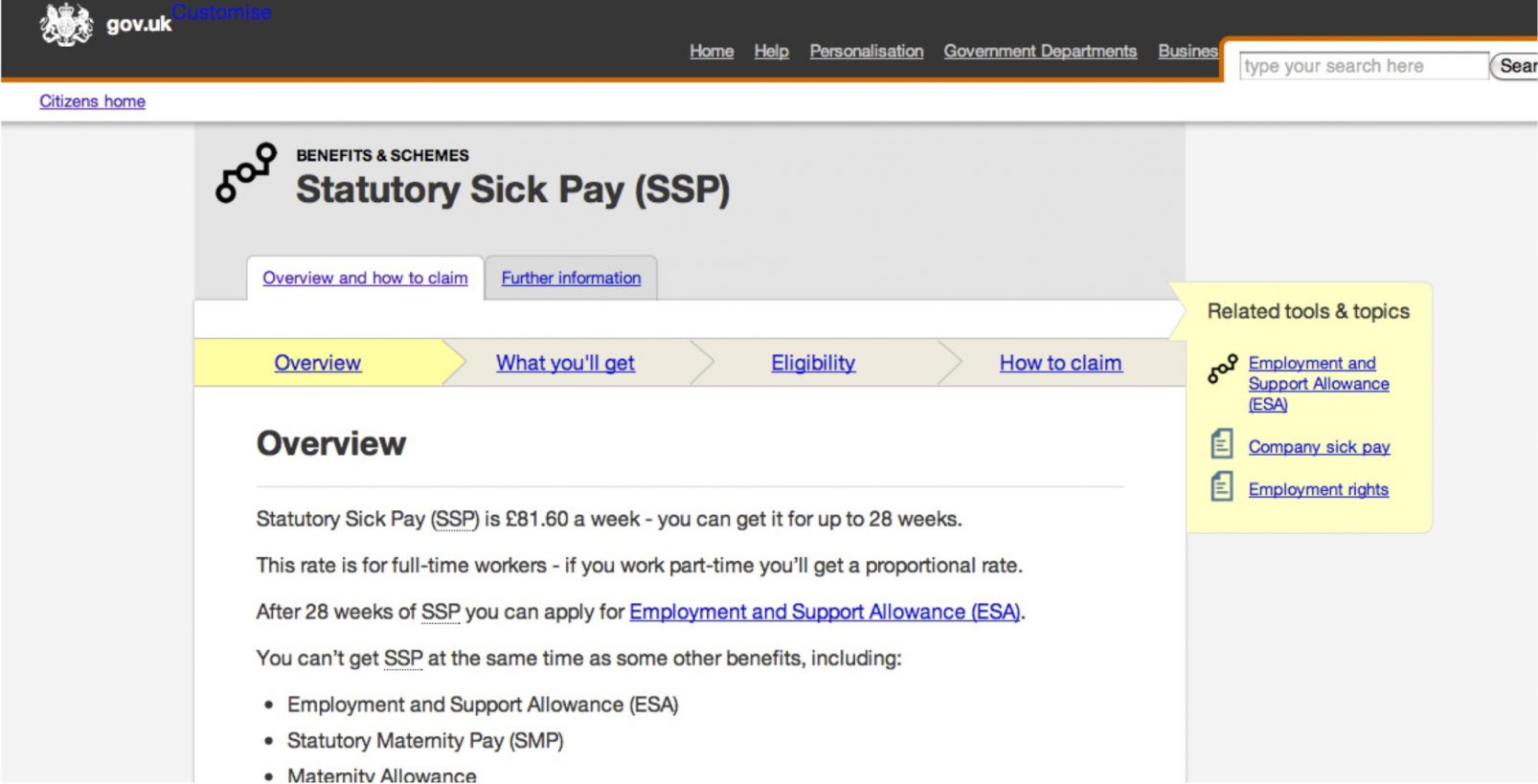

Another alpha page, this time for the Treasury's home page. The departmental news was presented almost like a Twitter feed.

A blog post by the alpha team's design lead, Paul Annett, explained more about the visual language they were considering at the time. They also wrote a colophon listing the tools they had used.

The alpha was about proving a point, not making a product. In that regard, it was successful. Within a couple of weeks, work began on the next stage: beta.

20 May

Mike Bracken was formally announced as the new Executive Director for Digital in Cabinet Office:

The role will combine the work of the Chief Executive of Directgov, the lead of cross-Government digital reform work and part of the work of the Director for Digital Engagement and Transparency. He will report to Ian Watmore, the Government’s Chief Operating Officer, be based in the Cabinet Office and will be responsible for over 100 staff in the Government Digital Service, of which Digital Engagement is part.

Behind the scenes, GDS was taking shape. Work had begun on scoping out the beta phase.

Like the alpha before it, the beta began as a mental map sketched on the wall.

July

Photo: Jamie Arnold

Work continued on the GOV.UK beta, which was planned to run alongside Directgov until the latter could be replaced. (The decision to replace it on 17 October 2012 was taken by James Stewart and Etienne Pollard over coffee early in 2012 - it was their second choice of date, after they realised their first choice would fall during political party conference season.)

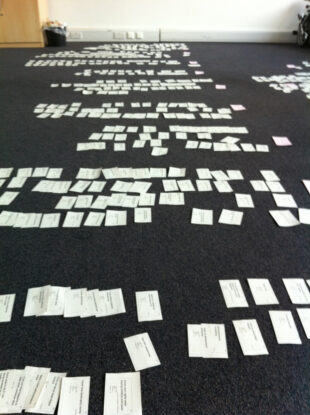

All the user needs were written on index cards, and the cards spread out on the floor – it was the only surface large enough to see them all in one place, and to sort them into categories and varying priorities.

Writing in 2016, Sarah Richards explained why and how she created the role of "content designer":

The one thing I was really enthusiastic about, was that digital content isn’t just words. Government really needed to see that its content people could do so much more than they were being allowed to. Content people should only limited to what the research shows is the best way for the target audience to consume that information. That could be a tool, calculator, calendar, video etc. Content should mean content, not words ... It was right then that we decided on the term ‘content designer’ for the British government.

4 July

The first sign of our "coding in the open" approach emerged. It was later described in a blog post by James Stewart.

29 July

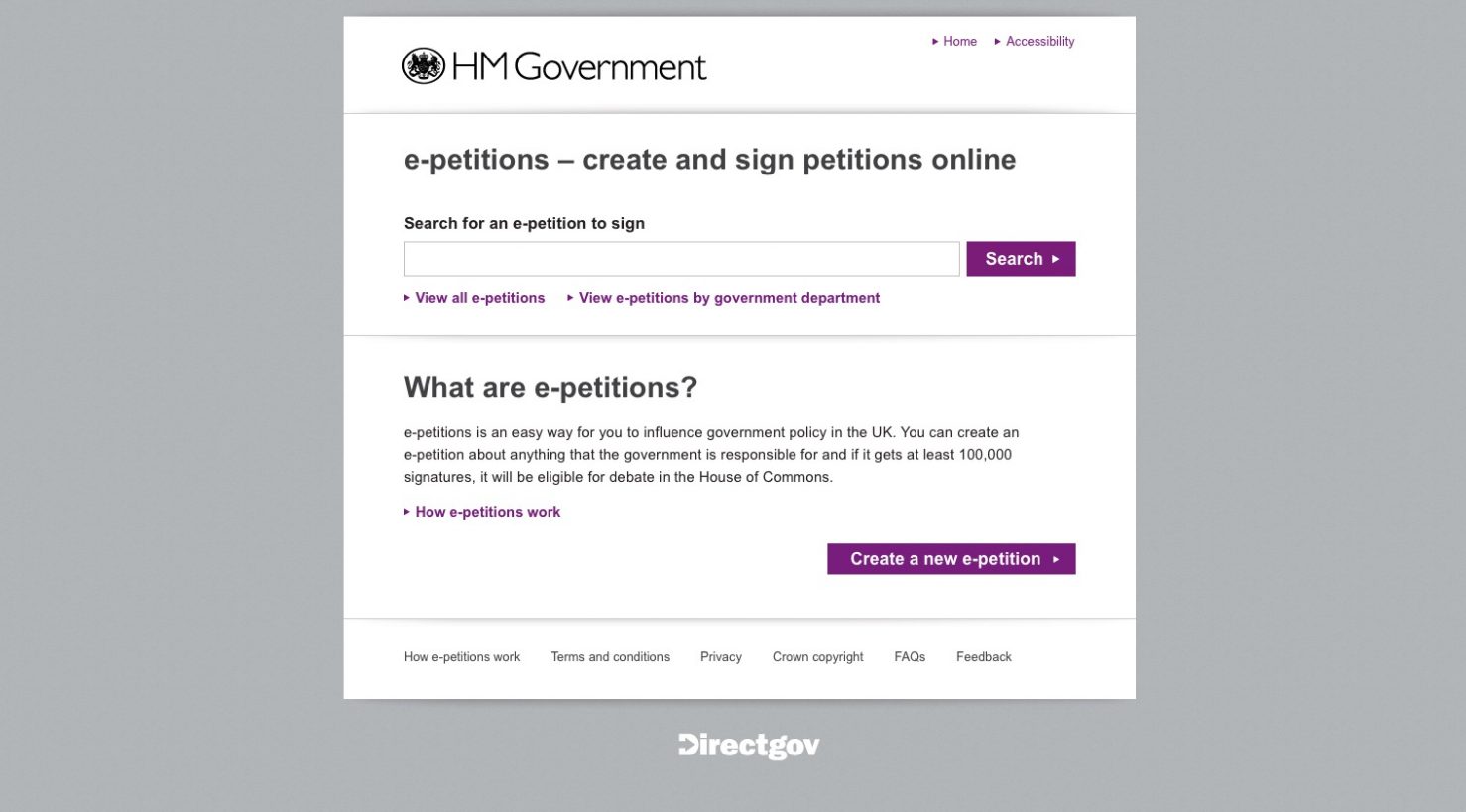

GDS delivered its first product: an online petitions service for government. It was built in 8 weeks by a team working in an agile way. This was a quick one-off project, a chance for the brand new organisation to show what it was capable of. The petitions service was updated and rebuilt by GDS, in collaboration with a team from parliament, in 2015.

On the same day, Mike Bracken wrote his first blog post, with the first hint of the work that would eventually become GOV.UK Verify:

The second key piece of learning for me has been how important it will be to have a federated identity layer across Government services... As citizens and users we all know that we generally view Government services digitally as being either locally or nationally provided, and that we often don't worry too much about the department responsible. Accepting that this user behaviour will drive the provision of cross Government delivery is a principle which has been played back to me repeatedly in the last 3 weeks.

August

During the summer, Mike Beaven joined the team. His first task was running a reorganisation exercise, matching people to roles in the newly formed GDS. Most staff had to reapply for jobs within the new team.

Another new starter in August was Chris Thorpe, who joined to help with strategic thinking, and explain it to ministers. He coined the line “Trust, users, delivery.”

10 August

David Rennie introduced the Identity Assurance project, which later became GOV.UK Verify:

We need better ways of establishing trust relationships in the digital era. We need better security than long lists of user names and favourite films. Our aim is to collectively address these problems through the GDS Identity Assurance Programme.

11 August

The GOV.UK beta was formally announced in a blog post:

We'll be building on the learnings from alpha.gov.uk, while filling in numerous gaps we left. For example, we want to make the most easy to use, accessible government website there has ever been. Merely ticking a box marked 'accessible' isn't enough. It has to be useful for everyone and usable by everyone.

The beta had 3 stated objectives:

- Public beta test a new site delivering citizen-facing content (known internally as "mainstream")

- Private beta test a new publishing platform (for departmental staff to use to add and maintain pages on GOV.UK)

- Develop a "global experience language" – a visual identity and clear user experience for GOV.UK

19 September

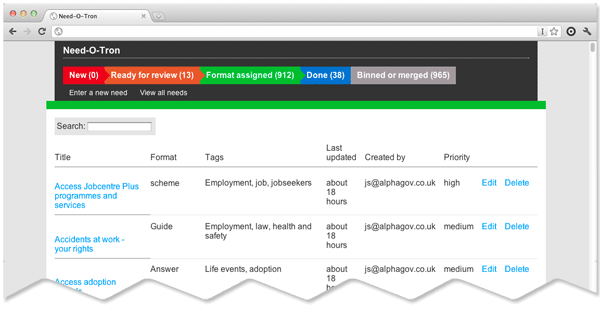

Richard Pope wrote about the Needotron, an internal tool the team had built to track of hundreds of user needs and the pages and page formats we thought could meet them.

October

Photo: Paul Clarke

Chris Chant, who had been interim leader of GDS before Mike Bracken’s appointment, delivered his now-famous "unacceptable" speech at the Institute for Government, criticising the existing state of government IT. Read a partial transcript.

I think it’s completely unacceptable at this point in time to enter into contracts for longer than 12 months. I can’t see how we can sit in a world of IT, and acknowledge the arrival of the iPad in the last two years, and yet somehow imagine that we can predict what we’re going to need to be doing in two or three or five or seven or ten years time. It’s complete nonsense ... It’s completely unacceptable not to know what systems we own, how much they cost and how much or even if they are used.

Later, he wrote a post on the GDS blog spelling out his plan for fixing the problems.

November

Photo: Jamie Arnold

GDS moved to a new office on the 6th floor of Aviation House in Holborn.

Ben Terrett and Russell Davies joined the team. Ben headed up the small design team, and began to expand it. Within a couple of weeks of starting, he visited the Garter Principal King of Arms to ask permission to use the crown on GOV.UK. Permission was granted.

4 November

We announced £10 million funding for the Identity Assurance programme (which would later become Verify).

10 November

Chris Chant invited small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) to come and talk to government about how GDS could work with them to level the playing field for all IT suppliers. Part of what would later become the Digital Marketplace.

1 December

Emer Coleman joined as Deputy Director of Digital Engagement.

8 December

Although almost a year of work had already been done, this blog post marked the official "opening" of GDS as an organisation: "We are open for business."

GDS hosted an opening event and invited the press (photos from the event). The coverage was very positive:

- Wired (as saved by the Internet Archive): Public services should be digital by default

- Telegraph: Failed web services cost taxpayer £1 billion

- Computer World: GDS launches