I’ve just got back from a few days in the Republic of Estonia, looking at how they deliver their digital services and sharing stories of some of the work we are up to here in the UK. We have an ongoing agreement with the Estonian government to work together and share knowledge and expertise, and that is what brought me to the beautiful city of Tallinn.

I knew they were digitally sophisticated. But even so, I wasn’t remotely prepared for what I learned.

Estonia has probably the most joined up digital government in the world. Its citizens can complete just about every municipal or state service online and in minutes. You can formally register a company and start trading within 18 minutes, all of it from a coffee shop in the town square. You can view your educational record, medical record, address, employment history and traffic offences online - and even change things that are wrong (or at least directly request changes). The citizen is in control of their data.

So we should do whatever they’re doing then, right? Well, maybe. There is a fairly unique set of circumstances in Estonia that have allowed them - and to some degree forced them - into this model of service delivery. More on that in a bit.

So, how does it all work then?

Underpinning the entire state system are two crucial things:

- a national register (called the Population Database), which provides a single unique identifier for all citizens and residents

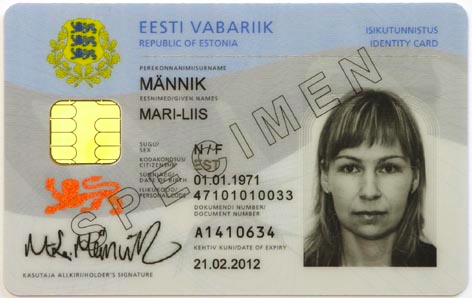

- identity cards that provide legally binding identity assurance and electronic signing

The UK has a fundamentally different approach to identity from many of our continental colleagues. One that doesn't involve ID cards, big government databases or general identifiers - more on the UK identity assurance work here. However, that doesn’t mean there aren’t wider lessons to take from Estonia’s digital ambition.

Government as a data model

As a general rule, government systems in Estonia are not allowed to store the same information in more than one place. Basic personal details are the most obvious example of this. So everything starts with the Population Database. Within this database for each person is a unique identifier, name, date of birth, sex, address history, citizenship, and their legal relationships. It is, quite literally, a relational database - the entire nation’s family tree can be visualised back until about 1950. The Estonians are confident the database is as close to 100% complete as it’s practically possible to get.

This profile of basic personal data doesn’t need to be held in any other system: they just need to hold the unique identifier. This distribution of data provides some degree of data protection – there is no one place where all the information about someone is held. Of course it’s useful to have someone’s basic details to hand when using local systems - like their name and address - and that’s where the data sharing layer, or the ‘X-Road’, comes into play.

The X-Road is a secure data sharing network, much like the Government Secure Intranet (GSi) used by the UK government. Each data owner determines what information is available and who has access to it. Couple this with some enforced data and messaging standards, et voila; you have joined up government. It’s basically how you would architect software, but on a macro level.

As can be seen in the diagram above, some parts of the private sector can also utilise the X-Road - allowing the principle of not duplicating data in different locations to flow out from government.

Putting people in control of their data

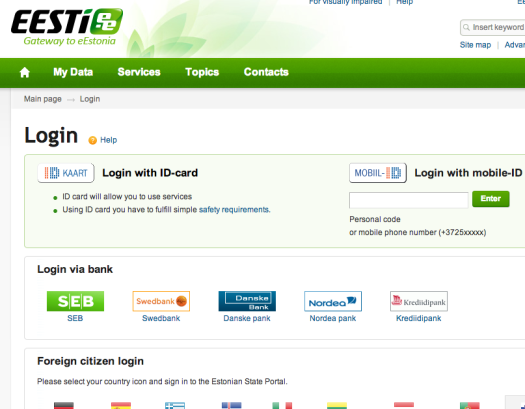

Citizens and residents can access nearly all of their own data online through the State Portal. There are around 400 municipal and state services integrated, and more are coming. You can log in, using your identity card and view all your data, even correcting things that are aren’t right.

Citizens can be associated with their employers, so it’s possible to transact and sign documents commercially using your personal identity. Business owners and board members are associated with their companies, and this data is openly available. Even land and property records are open for anyone to view. To demonstrate this, we were able to look at the President’s information and see the nice big block of forestry he owns in the countryside. Such transparency seems to increase trust in the whole system.

The volume and richness of this data, coupled with the common standards used to publish it, lead to some very impressive visualisations and visualisation tools for people to use. It’s possible to enquire about a company, see who the directors are, see what other businesses they have an interest in, see what the turnover and financial reports are, what land they own etc. It’s not just that all this data is publicly available: it’s also that the data is made easy to traverse with well designed visualisation tools.

How Estonian electronic identity cards work

Identity cards serve as both a physical identity document (they contain a photo and biometric data) and an electronic identity. Each card contains a chip. On this chip there are 2 digital certificates: one for identity and one for digital signing. The two digital certificates are each protected by 4 digit PINs.

The typical usage pattern is to log in to a service using your ID card and identity PIN (card reader required). A positive – or negative - response is then sent to the service. Then if you need to submit something during the session that would normally required a signature, you enter your electronic signature PIN. Finally, your time-stamped digital signature is created.

More recently they have introduced a SIM card equivalent, so you don’t need a card reader. You get a special SIM card containing the digital signatures, and your phone acts as the card and card reader combined. People can just sign in to services using their mobile phone number. This is expected to be very popular.

This identity assurance is also used commercially, initially by banks, but its use is now pretty widespread. It’s used for travel on public transport, so you don’t need to carry an additional card. Just purchase your ticket or weekly pass in advance and if a transport inspector wants to check you’ve paid, they just can scan your card to find out.

Who’s watching the watchers?

There’s an open register showing the profile information that is held in each government system, what reason it is held for, and who it can be accessed by (well, it’s open if you read Estonian). This register also shows the formats and data standards that each system is using.

People in Estonia can also see which officials have viewed their data. It’s against the law to view someone’s data without appropriate reasons (you could go to prison), and all access is logged. I looked at some of these logs and they show you clearly who has been looking at your information: in the example I was shown, I could see that a doctor had accessed this person’s health records, followed by a pharmacist to get details of the prescription required. No bits of paper are needed.

Of course, it’s technically possible that some official somewhere could have access that doesn’t leave a footprint. I was assured this isn’t the case and that the systems as a whole are independently audited regularly to ensure trust remains high.

They quite literally can’t afford for people to lose trust in this system.

Why Estonia?

So, how has Estonia managed to do this? Well, a number of reasons. Firstly, it’s a small nation – with just over 1 million people living there – so it’s relatively quick to roll out change. They are also not a nation with large tax revenues, and there are not a lot of natural resources (forests aside). So the state needs as much efficiency and as little bureaucracy as possible.

Possibly driven by the timing of their independence from the Soviet Union (1991), the Estonians saw technology as crucial to establishing and running the country. It was, and continues to be, an astute group of political and civic leaders with the vision and determination to make the most of the technological opportunities available.

So what’s next then?

Much of what Estonia has achieved was possible because they started with a clean slate.

We don’t have that in the UK, but the visit convinced me that we need to increase our focus on two really important things:

- collating, documenting and publishing details of the data the government holds (and what format it’s in) for each of our systems

- publishing an agreed set of open data and messaging standards and protocols, to allow easier communication between systems (where that’s appropriate)

Work is underway on both of these things - expect to hear more very soon.

It’s important to get this right: along with our identity assurance work, it will make joined up digital services much easier and cheaper to deliver. So we’ll be able to really focus on making the services as good as possible for our users.

Pete Herlihy is a Product Manager, GDS

You should follow Pete on Twitter now: @yahoo_pete

31 comments

Comment by Bharat posted on

I think UK is challenged with the 'Keep the heritage intact while innovating' framework which makes it difficult to make sweeping changes for the betterment of society. Someone, somewhere has to let go first and things can move rapidly.

Comment by Pete Herlihy posted on

In reply to William at Mydex.

Thanks William. “The citizen is in control of their data” was really a comment about people having real-time access to and visibility of the information that the government holds on them (and the ability to amend errors).

I accept isn’t the type of control you describe, where people can decide which data, if any, needs be shared with the government for certain things – but compared with the starting point for many, it’s a significant increase in control.

As I noted in the post – and you’ll be well aware – the UK has a fundamentally different approach to identity than Estonia and many other European nations. I would expect that yes, we will end up with a solution that for us, is a ‘better place’. If that ‘better place’ is a range of disparate data, held in different citizen controlled places and used for different interactions (identity, data provision), then yes, the citizen will really be in control of their data.

Estonia has the disparate data model, the difference is that it’s the State that holds the all the sources, and the other sectors that come to it for the data or identity assurance.

Comment by William at Mydex posted on

Very interesting article. It's great to see GDS is sharing insights with Estonia. Also good to see data architects reflecting about cultural differences; code is law after all.

I'd just test your assertion

> The citizen is in control of their data.

What you describe is a way of working where the citizen can see and use their data, but the government controls it. But the UK ID assurance approach supports what Mydex has built, which is a model where the citizen genuinely is in control of their data. Only the citizen or individual has the encryption key, and only the citizen or individual (not the government, the bank or the community interest company Mydex) can authorise the sharing of data to complete the online forms or provide the verified assertions necessary to get a public service.

Do you agree it's a key distinction? And that the UK is therefore potentially in a position to muddle its way through to a *better place*, more quintessentially British perhaps, than the clean single central government database model which evidently works well and is culturally acceptable to Estonians?

Only the truly citizen controlled model opens up the far greater benefits that lie beyond efficient public services: a new holistic economy of online services (private, public and third-sector) based on volunteered personal information from the individual. Government services and open data are only a small part of the full set of real services we need and want after all.

I contend that GDS' ID assurance architecture working with personal data stores such as Mydex supports that deeper long term outcome fundamentally better. That's not to say it's easier to do than what Estonia has done. And, as you say, we start from a more complicated place, with a cultural past we are less willing to abandon.

Comment by Making transparency data more transparent with a CSV preview | Inside GOV.UK posted on

[…] one year on Improving browse and navigation Government as a data model: what I learned in Estonia (GDS blog) How many people are missing out on JavaScript enhancement? (GDS blog) Do we need […]

Comment by A time for sharing (government content on Facebook and Twitter) | Inside GOV.UK posted on

[…] GOV.UK goes to Estonia (GDS blog) […]

Comment by Gary Ling @GarysBalls posted on

This is a really informative post thanks. Assuming the taxpayer paid for this trip it seems we got good value for money. I particularly like your observations that:

"Much of what Estonia has achieved was possible because they started with a clean slate. We don’t have that in the UK, but the visit convinced me that we need to increase our focus on two really important things:

+ collating, documenting and publishing details of the data the government holds (and what format it’s in) for each of our systems

+ publishing an agreed set of open data and messaging standards and protocols, to allow easier communication between systems (where that’s appropriate)"

...and your assurance that:

"Work is underway on both of these things – expect to hear more very soon."

To make the most of both of these developments the issue of data privacy needs to be addressed. At present, it seems that many policymakers across government are wary of even using and sharing anonymised aggregated data which would transform the ability of the public sector to provide really targeted and useful services.

Indeed, one of the biggest issues the UK faces in getting close to the 'joined up thinking' you describe in the provision of government digital services in Estonia, is legislative restrictions on how data can be used and shared between UK government departments, local authorities and agencies. The Digital By Default strategy alludes to this in some way when it says the Government Digital Service will :

"5) Remove unnecessary legislative barriers

The Cabinet Office will work with departments to amend legislation that unnecessarily prevents us from developing straightforward, convenient digital services."

Perhaps you or someone else in the GDS can post exactly how they are going to tackle this given a busy legislative timetable for the Coalition. Does Francis Maude have the political 'pull' to be able to table a bill that brings the whole government into line, from a data protection point of view, with what is required to make UK public sector digital services truly fit for purpose, cost effective and highly targeted? Or will we see a sub-optimal, piecemeal legislative effort where such changes are hacked onto bills that only affect individual departments and functions? When the GDS can tell us this it will mean that they have truly recognised that Digital By Default is a lot more than data standards, procurement changes, technological innovation and User testing. It's really about transforming how individuals perceive the return they get on sharing the marks of their digital footprints.

Comment by Colin Morton posted on

What is also very impressive is the extent of their wifi coverage to enable access to these systems and others. There's even access in the forests. More here: http://estonia.eu/about-estonia/economy-a-it/e-estonia.html

Comment by Tero Tiainen posted on

Please Please more articles like this!

This is somewhat disturbingly beautiful how good can systems be when they are done right.

What still intrigues me - what are the downsides of this? There has to be some sort of information about downsides and what limitations they create in service development.

I can think that it's quite horrendous for people if they lose their ID card _and_ pin code..

Comment by Graham posted on

So what 'appropriate reason' did you give for viewing the President's record?!

Comment by Pete Herlihy posted on

Land and property ownership is open data, so no need for a reason to view that information!

Comment by Markus posted on

About the question rised in article "How did they do that?" and a given answer - "Possibly driven by the timing of their independence from the Soviet Union (1991), the Estonians saw technology as crucial to establishing and running the country. [...]"

Mr President of Estonia said ca year ago in IT conference, that most of these results are achieved NOT THANX to politicians but rather politicians did NO TAKE IT as serious topic and did not start a fight around it. So - the specialists could just do the work.

Comment by Reteep Tevram (@petskratt) posted on

regarding wathcers - the e-health is possibly the only system that provides easily accessible log, but quick look at my own account shows that only part of my data is handled by this system - meaning the rest of accesses is not easily findable...

I have used another register myself to demonstrate the possibility of seeing access to my data in past years, but when police, borderguard & immigration were brought under same roof something has changed in this single example of accountability - perhaps all of the access is now considered to come from police and hidden. And yes, even before it was only showing partial access - I recall being stopped by traffic cop who was able to prove my identity when I had managed to forget all documents at home (which is actually fabulous achievement), but that access did not show up.

So currently we have one system with usage log - and the system is far from covering all of the data on this field. If you find somebody able to prove otherwise - please let them know I'd like to see the presentation as well.

Knowing estonian language and having tried to use the mentioned open register of registers - it mostly contains metadata like laws mandating the creation of register, finding information about actual data held in a register is often impossible (or perhaps just very complicated).

Knowing also a bit about british scepticism - next time in Estonia please ask to be introduced also to local sceptics, perhaps you need that information as much as the positive stories, either in your relations with sceptics ... or more importantly - developers 😉

btw - in case somebody here is interested to see how Estonian e-voting looks from the screen of real voter I did a screencast http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CnjmAhyUbis

Comment by andrew coulson posted on

Pete,

A really interesting article. As someone with an interest in Digital Inclusion but not much knowledge of Estonia I wonder how many of their citizens access their online services? Does everyone in Estonia have access to the internet and equipment and do they all have the skills and confidence to use the online services? Did you speak to many of the 'end users' about how they found the experience?

Comment by Jaan posted on

You can find some insight from https://www.ria.ee/facts-about-e-estonia

Just some highlights:

In 2013, 95% of people declared their income electronically. This is my favorite e-gov service 🙂 Usually it takes 2-5 minutes to submit my income report 🙂

During parlament election 2011 24% of votes were given electronically.

Comment by Markus posted on

Dear Andrew

I saw your question and asked Google to help me a bit 🙂

In May 2006 Statistics Dep of Est found that Q1 2006 38,7% of all households in Estonia had access to Internet.

In Q1 2012 75% of households had access - it means they have computer and a connection, Amongst families with children the number is 90%.

The amount of people using Internet amongst 16-74 years is 78,4% (in 2011 that number was 76,5%)

Comment by Steven posted on

In de mid-90's, There has been a quite important effort to train people in the basic use of computers and the internet. Add to that the ID-card as a trusted solution and attention for digital solutions "all the way", and the high take-up becomes more of a natural thing.

To understand how everything came together, one should not forget where Estonia was coming from - a newly independent corner of the Soviet Union with not much infrastructure but a lot of technological know-how. On that basis, the choice was made to try and jump forward and to skip a few steps. The political will was much more important than the funding.

Much more about this is here: http://e-estonia.com/e-estonia/how-we-got-here

Comment by Richard posted on

Peter, I'm not sure I agree with your comparison of X-Road being similar to GSI.

GSI is a network... Whereas X-Road is a data exchange layer.

X-Road is much more akin to the Government Gateway Transaction Engine (i.e. uses GovTalk for data standards and XML, HTTP, SOAP etc. for messaging standards. In fact underneath the covers, X-Road looks very similar.

You may want to investigate a little more closely.

Comment by Andreas posted on

Hey there,

just for an extension to this picture, check out this article:

http://news.err.ee/Opinion/07c50ec4-bf64-403e-b4e6-0dfbe4e1a30b

It's an opinion paper by a colleague of mine.

Comment by Kaur posted on

When reading the article by de Voogd, please focus on the first sentence:

"There is a theoretical flaw in the Estonian ID card system".

THEORETICAL.

De Voogd speculates about smart cards not working the way everyone believes they do work. The article can be summarised in one-sencente quote:

"How can we trust that we have the only copies of the secret keys on the ID cards - secret keys that we did not create, that were issued to us by the state, and that we cannot replace with self generated keys?"

So, WHAT IF the private RSA generated in a smart card - is not really private?

This is an accusation to all ICC vendors in the world, and not to Estonia or its government.

Comment by Pete Herlihy posted on

Thanks Andreas and Kaur,

This post isn't intended to get into the pros and cons of identity cards - as I mentioned, we have a very different philosophy to identity assurance here in the UK.

It's really interesting (and perhaps not surprising) to know that there are different views, so thanks for posting.

If there are more comments received for or against identity cards, I hope people aren't offended if I don't publish them here - that's a much bigger debate for a different blog!

Thanks, Pete.

Comment by Triin posted on

"ERR News recently published an opinion piece by Internet freedom advocate Otto de Voogd that called into question the security of Estonia's much-touted ID card system. The following rebuttal is from Agu Kivimägi, head of the cyber security department at SMIT, the Interior Ministry's IT and development center, in response to our request...." http://news.err.ee/Opinion/16ecb27f-74eb-4b91-b78d-a685c2776f13

Comment by Chris posted on

Correction: for authentification the PIN is 4 digits and for signing it is 5 digits. Otherwise pretty precise overview. Well done Pete!

Comment by Konn posted on

PIN for signing - variable length, usually 6 digits.

Comment by Indrek posted on

The PIN for authorisation/signing can also be 6 digits.

Comment by Benjamin Rusholme (@benrusholme) posted on

Interesting, the richness of the data and the ease of use for estonians is inspiring. The city of Tallinn looks beautiful.

Comment by myluit posted on

useful update on the digital advancement .

Comment by Clive Walley posted on

Yes, I know Tallinn - it is a beautiful city and quite like the old part of Riga, the Latvian capital.

For a country that was occupied by one of the most oppresssive regimes in recent history they have worked wonders and as you say on such a small budget.

The UK is immeasurably richer but its governments waste great swathes of taxpayer's money on drafting endless legislation to limit and reduce the basic freedoms of its populous.It is only in recent years that the public has had access to its own medical records for heavens sake and was previously told it was not their business to know! However did we practice Habeas Corpus before? This freedom of information was thanks to the EU and not the free choice of the legislative.

The archaic state of the voting system and the lack of any real conviction to change it makes our country look third world. We can buy a lottery ticket at a booth or shop and the result is known within seconds of the draw by the organisers including the number and names of winners, etc. Our general elections are an embarrasement with thousands of people sifting, counting, stacking and then often recounting, resifting and restacking of ballot papers. Simple electronics could make polling stations the true relic of the past that they are and the massive costs of employing hoards of people to count the ballot papers, redundant with a real cost saving.

In contrast the streets are littered with spy cameras at God knows what cost and whilst they do help sometimes in crime solving, they make the general public feel that their government does not trust them. The balance is all wrong and until we move foreward from the 19th Century we will remain something to be laughed at.

It takes a little courage but just copy what the Estonians have done and bring on electronic online voting for all UK citizens including those who have been so cruely treated and disenfranchised so that they can no longer vote.

When Mr Cameron visits Sri Lanka and spouts about fairness and justice to other nations I'm sure that some of these countries will be asking "How dare the British talk to us this way when they disenfranchise their own subjects from voting in elections and referendums?".

Comment by simonm posted on

You're right that there are many areas where Digital by Default is the only sensible choice, but voting isn't one of them.

Paper-based, turn-up-in-person ballots remain the safest and most transparent system - that's what democracy needs. Right now there is a crisis of trust in the democratic process, acknowledged by all political parties. The much vaunted ease of digital voting doesn't help this, simply because, if there are sufficient funds available, corruption can be made untraceable. The more humans involved in the process, the harder it is to suborn them and the safer it is. Postal voting "reforms" have been a disaster in terms of corruption, and that fact isn't lost on a cynical public. I have personally seen how easy it is to obtain and use ballot papers fraudulently in local elections. The beauty of the old system is how hard it is for a fraudster to not leave a trail behind.

I mentioned funds: the police will readily tell you how elaborate (and expensive to initiate) bank frauds have become, from hardware to trap card data on cash machines, to insider thievery by those who know system details. We can't go back to a world where the cashier recognised your signature (in ink!) on a cheque, but the price we pay for easy electronic trading is a not-insubstantial level of dishonesty, and often financial disaster for individual victims (schemes don't always pay out!).

That has direct parallels with an electronic election system.

Of course the process has a price, but it's small compared to the price of unsafe elections. All electronic trust systems depend on accurate identification in the first place, and that in turn depends on human identification. Unless/until we bond some sort of genuinely unique identifier to each human, which lasts from birth to death, the flesh-and-blood part of the process is vulnerable, as is the technology. It's politically impossible presently to adopt the Estonian model of identity cards (and note that they only have a 4-digit PIN in any case!), and that makes e-voting practically impossible (if it's also to be safe!).

As for the disenfranchised, some problems are very hard to fix. And in any case, that too is a political issue--who should the electorate be? Is it those who live here, those who have Citizenship, those who have "roots" here, or perhaps even more controversially, those who pay £x,xxx per year in taxes? There are other alternatives too, and your preferred definition may not be mine!

And the bigger issue by far is getting services extended to those in greatest need, for whom digital voting would probably be an enormous challenge.

I'm no luddite! I blog on technology for SMEs for an IT services company in Bristol, and I'm an enthusiast for Digital by Default, but "a man's gotta know his limitations," as Harry Callaghan put it. I'd prioritize safety of elections way higher than anything else.

Comment by Katrin posted on

Correction: 4-digit pin for logging in, 5-digit pin for confirmation.

Comment by Dave Tego posted on

I visited them in 2004, I was relly impressed with their PArliament, where over ten years ago, it was all broadcast and totally digital. Each member had a terminal in the chamber, all of the voting was electronic. Citizens could watch it in real time via the Internet.

I thought GSI had been replaced by the PSN?

Comment by Pete Herlihy posted on

Yeah, good spot Dave. GSi is *being* replaced with PSN.... I'm not sure when it will be finished though.