We’ve talked about registers as authoritative lists you can trust, but what do we mean when we say “register”?

Across government we manage and hold data that we need to deliver services to users and to inform policymaking. We make that data in a variety of ways — from bespoke online tools, dumps of databases, through to published lists. A question we’re often asked is:

What is a register, how is it more than just a database, a statistical report, or a simple list?

To try and answer this question we’ve started to collect a list of characteristics based on the things we discovered during our early discovery and alpha work.

Some of this gets a bit technical, but we think that’s a good thing. Getting the technical stuff right at the start is an important first step.

These characteristics will be refined in the coming months as we learn more by working with people to build beta registers, but here is our first attempt to list them.

1. Registers are canonical and have a clear reason for their existence

A register is the only authoritative list of a specific type of thing. It is the source of that information, kept accurate and up-to-date. For example, the company register administered by Companies House should be the single, authoritative place to go to find data directly related to a limited company such as the date it was formed and the date it was dissolved and a link to the registered office.

The purpose of a register should fall within the bounds of a registrar’s public task — its core role or function.

2. Registers represent a ‘minimum viable dataset’

A register only holds the data it was created to record, and nothing else. It never duplicates data held in other registers. Registers link to data in other registers to avoid the need for any duplication.

To make those links work, each record in a register must have a stable, unique identifier. For example, registers should use the ISO-3166-alpha-2 country code to unambiguously reference a country, relying upon the country register to hold the country’s official-name, local-name and other information for the code.

Registers are long-lived because services and other registers depend on them. A register is just the data. It is the role of services to present data in a variety of different ways which make sense to users.

3. Registers are live lists, not simply published data

Registers are digital and may be accessed or searched by humans or machines using an API. The same data may already be periodically published as a document on a website, but that is not the same as operating a register.

For example, it would be difficult for a developer to use the PDF of sports governing bodies as a selection on a visa application form. They would have to notice when the document is republished and repeat the same work of downloading and processing the document whenever it is updated.

Making changes to a register shouldn’t take long; at most a matter of hours to give custodians the opportunity to check a new entry and guard the register against fraud and error.

Registers should have a standard interface for reading and querying their contents, which follows the API principles set out in the service manual.

There should be a clear process for challenging data held in a register with high standards for transparency, adjudications, and the processing of other issues discovered by users with register data.

Register data should be available in a variety of different standard representations, including JSON for Web developers, comma-separated values (CSV) for people working with tabular data tools like spreadsheets, and RDF for those with needs for linked-data.

A register API should be highly available. Public register data should be cacheable by intermediaries and web clients to enable the incorporation of the register directly in live services, as well as being easily downloaded in bulk for offline applications, and updated using a streaming API.

4. Registers use standard names consistently with other registers

Wherever possible a register reuses standard names for fields to enable discovery — find all registers containing a “company” field, and search — find all the records in all public registers containing “school:1234” or “company:9876”.

The data held in a register may evolve over time: new fields may be added to new entries in a register so long as they have a sensible default value for entries, and existing field names are not used for a new, different purpose.

5. Registers are able to prove integrity of record

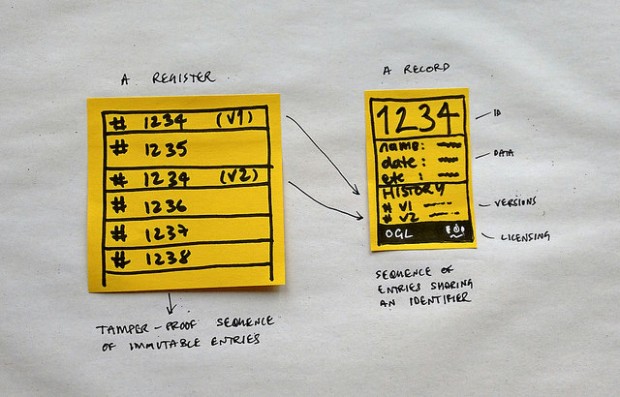

Each individual entry in a register is immutable, addressable using a ‘fingerprint’ which may be used by a user as a digital proof of record.

A record in a register is a series of entries sharing the same identifier. The latest entry being the current value for a record. Older entries for a record must remain addressable, but their contents may be removed if instructed by law.

The record of changes made to a register is transparent and independently verifiable.

6. Registers are clearly categorised as open, shared or private

The privacy of a register should be clear, and either open, shared or private:

- open registers are public. The data may be accessed, copied and derived freely, by anyone, either as single register entries or as a complete register, with clear licensing terms designed for reuse

- shared registers allow access to a single register entry. There will be some form of access control, such as having an access token, paying a small fee, or signing-in in with GOV.UK Verify

- private registers contain sensitive information which cannot be accessed directly by services. They may be able to provide answers to simple questions, subject to access control such as “Is the registered keeper of this boat over 21 years of age?” without revealing further details about the individual

- a closed register contains data private to a single organisation, is locked away, and not connected directly to a digital service

Following the Identity Assurance Principles means we don’t anticipate a single register of people, but registers may list people against specific roles. For example, DVLA should continue to maintain a register of drivers and a register of keepers of a vehicle.

Public registers should not reference private registers. For example, whilst the headteacher of a school may expect to appear in a public register of educational establishments, and have their name appear on a sign outside the school, they wouldn’t expect their passport, driving licence, tax reference codes or National Insurance number to be made public.

7. Registers contain raw not derived data

Data held in a register should be factual raw data, not informational content, or counts, statistics, and other forms of derived data.

8. Registers must have a custodian

A register should directly meet a user-need or legal obligation.

Someone is responsible for each register, as with The Public Guardian, The Chief Land Registrar and The Registrar General.

We'll be refining these characteristics as we continue our work on registers and we'll keep you updated on our findings.

Follow Paul on Twitter and don't forget to sign up for email alerts.

17 comments

Comment by Craig Snyders posted on

Sounds like a great place to use BlockChain to democratically distribute authority and data integrity verification.

Comment by Alison Gibney posted on

Hi Paul. Agreed, but the digital preservation of databases is a major headache. The more complicated they are the more difficult it will be to make the data available in centuries to come. That's why I'm thinking we need to take snapshots, as a flat file is much easier to make readable (and even print out) than a database, but somehow these flat files must include the history of changes.

I think the design of digital registers should build in preservation features such as reports or exports in a preservable format.

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

Ah, I'm with you now! Although the integrity of record is preserved using cryptographic techniques,, the actual register data is very simple plain-text, akin to CSVs, and long-term digital preservation is definitely something we strive to support.

Comment by Alison Gibney posted on

I think the list, especially 5 (the ability to prove integrity of record), is a list of desirable features but does not define a register.

A particular problem for records management is, if the history of a register is not contained within the register (a useful feature of the National Land & Property Gazetteer for example) then we have to take snapshots for the record. But if entries come and go within the month or even the day ( I am thinking of registers of doctors and dentists for example) what do we keep for posterity?

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

Hi Alison. There are some use-cases for redaction from a register, but we see keeping the history of every change made as a key part of improving the trust people may place in a register. A register which can be changed for a short period and then changed back can with no record of the changes made can be easily used to conduct fraud or other mischief.

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

.. by "easily" I meant "more easily" ..

Comment by Kevin Marks posted on

An example of a register that is open and in widespread use that is in html table form is

http://microformats.org/wiki/existing-rel-values

Comment by Kevin Marks posted on

Why mandate CSV when you could mandate tab-separated and save so much later pain?

Also, mandating html tables is probably more useful than mandating RDF. Anyone who wants RDF will be able to transform json into it.

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

Hi Kevin.

Generating multiple representations from a register is relatively low cost, but has benefits to users.

The main purpose of mentioning formats such as CSV and RDF was to highlight the need to support multiple representations. JSON is fine for developers, but not so useful to people inside and outside of government using spreadsheets. Similarly, citing RDF highlights how we are making data with links.

I share your preference for tabs separated values, and tend to convert CSV to TSV when hacking data so I can use Unix shell tools: http://blog.whatfettle.com/2014/10/13/one-csv-thirty-stories-bootstrapping/ but TSV isn't great at representing data containing line-feeds, and some of our fields can be "notes" containing content.

I've been a long time advocate of microformats and semantic HTML, but TSV/CSV is preferred by many users for dumps of bulky datasets, and some registers will have tens of millions of rows.

Comment by Saurabh Singh posted on

By RDF do you mean Resource Description Framework and presenting the data with knowledge representation?

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

I'm not sure what you mean by "knowledge representation", but we've demonstrated how an entry in a register can be represented in various different representations including the Turtle/N3 RDF serialisation with links for field names and value. The users and their needs for RDF are something we can blog about after we've learnt more from users.

Comment by Kevin Lake posted on

In a number of places you make the leap from Register, to Digital Register. For example, the register of births, deaths and marriages, is not able to provide a digital proof of integrity (number 5) because it is not a digital register, but this does not take away from the fact that it is obviously a Register.

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

It is true that we're using an existing word "Register" to describe something new. "Digital Register" is one of the names we're considering using to be more precise.

Comment by Will Hamill posted on

This looks very interesting, but seems to me that this would imply that a pre-requisite for creating a register that both avoids duplication and links to other registers for canonical entries is the agreement of domain terminology for things like 'company', 'school', 'vehicle' etc and an understanding of which register would contain ownership of those entities.

Many different agencies and departments will already have different views of what these nouns represent in their domain. Will only Companies House be permitted to define a 'company'?

If so, if for example the DVLA want to make a register with 'vehicle' given that they own the vehicle record responsibility, would DVSA need to delay work on a register of MOT Tests until DVLA agree on the common definition of vehicle for them to reference? They would presumably need to at least exclude any information on dvsa-vehicle that is already included in dvla-vehicle. Does this deduplication not also imply coupling so that to make practical use of DVSA's register of vehicle tests then the DVLA register of vehicles would need to be used by any consuming client?

If not, is this somewhere the use of "wherever possible" lets exceptions and edge cases through to avoid the co-ordination cost between departments and agencies?

Comment by Paul Downey posted on

Something we have found to help is keeping the scope of a register very tight, and bound to a domain. So there could be a register of limited companies (run by Companies House) and a register of courts (run by Ministry of Justice) and a register of schoos (run by Department of Education)

A licence could be issued to "company:xxxx", "court:yyyy" or "school:zzzz", linking to the appropriate register.

In our current alpha we're using a register of fields (names) and a register of registers to coordinate names, but haven't got as far as working out what the process would be for deciding which names to use. As the old joke has it, naming things is one of the hardest problems in computing ..

As for the dependencies between registers, in your scenario, nothing would prevent DVSA from creating a register of MOT tests containing a vehicle number, and storing either storing the other details about the vehicle separately, or accessing them through another API. The links to the DVLA register wouldn't be activated until the DVLA register became established, at which point the separate data /may/ no longer be useful.

Comment by mark pinheiro posted on

The type face used looks clumsy and is difficult to read in some places. In the word created, it looks like creat ed. See st at ist ical = statistical. Or is it my old browser?

Comment by Louise Duffy posted on

Hi Mark, could you let me know which browser (and version) you're using. It's rendering fine in chrome, safari and firefox for me so it might be due to your browser.