Government has always run on data. It drives internal operations, public-facing services and informs policy. Over time, an ecosystem of applications and technologies which store, manage, and access that data has developed. It includes spreadsheets, published PDFs, large databases, and a host of things in between.

This ecosystem isn't the result of a grand design. It’s the result of a series of pragmatic decisions made in the context of individual organisations and services, based on (mostly internal) user needs, cost, and available skill sets.

For the most part, that’s exactly the right way to do things – we learn what works by trying things out. But, as the demand for trustworthy, open data increases for the delivery of cross-departmental services and policy, we need to develop a more coordinated approach to data storage and access.

Expectations are changing

People’s expectations are changing. Not just of government, but of any service provider.

There are lots of practical implications of this for government. For one thing, service users rightly expect from government the type of streamlined approach to service delivery they already enjoy when dealing with modern digital businesses. For example, it’s reasonable to ask why more government services don’t re-use open data that’s managed by another part of government.

Aside from government reusing open data for the provision of its services, there’s a growing expectation of reliable access to government data by other organisations to provide complementary services. So, third-party applications like MunchDB, which reuse food hygiene standards ratings data collated and published by the Food Standards Agency, should become commonplace.

Government’s data infrastructure needs to change too

Improving access to data has been a government priority for a number of years now. Through the creation of data.gov.uk, over 20,000 datasets have been made available, under an open license. Access and discoverability have improved.

But, we publish datasets, and in some cases more than one version of a given dataset, in multiple places including GOV.UK and the Performance Platform. Publishing across the government digital estate isn’t a bad thing, we should publish wherever best meets user needs. But as the range of data available increases we need to continually ensure we make it easy for users to identify authoritative and, by extension, reliable datasets - in terms of availability and format consistency.

It would also be great if more of the data that government publishes across its digital estate had a verifiable history. Otherwise, it can be difficult to see how data has changed over time, or trace its provenance.

Without assurances like these, using government data as a basis for digital services is a challenge for service teams both inside and outside government. Also, APIs – technical rules that specify how software components should interact – aren't consistently available. If they were, this would also go a long way to making government data easier to integrate into web services.

The limitations of government's current data infrastructure also affects data publishers and policymakers. Data publishing isn't always a priority. As a result, it is often irregular, resulting in stale, out of date data that reduces that quality of any decision-making based on it.

Internal and external data users need a data infrastructure able to provide three things:

- reliability: will accurate and up-to-date data be there when needed

- predictability: will data retain the same format, and will it be consistent with other datasets

- coverage: will the dataset be comprehensive for what it claims to cover

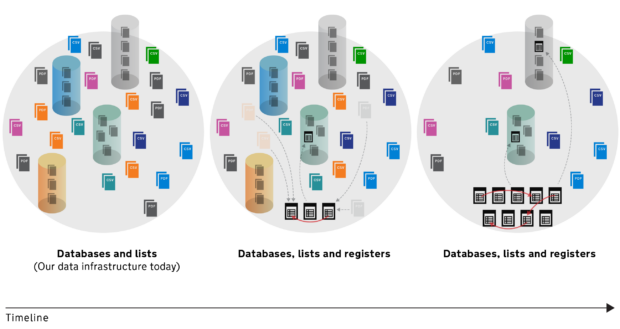

A new data infrastructure and new ways of doing things

The simple truth is that much of government’s current data access and storage infrastructure can’t support the emerging needs of its users. The work we’re doing on digital registers is one of the ways that we’re looking to better meet some of those needs and provide accurate, authoritative sources of data. Paul Downey has written about the early-stage work we’re doing on digital registers. And there will be more to come.

Registers won’t meet all government data storage needs

Not all government’s data will need to be stored in registers. Some data relates to process and management information, not ‘things’. For example, data about processing applications and service requests (generally labelled ‘casework’) isn’t appropriate for storage in digital registers because it usually relates to changes in state on the way to an outcome, and is rarely used by other organisations for reference purposes. Instead, it’s the outcomes of these processes that may become digital registers: for example a list of organisations’ food standards hygiene ratings, or a list of premises licensed to serve alcohol.

Digital registers are designed to meet the needs of users as much as the needs of the data custodians. That makes them less suitable for storing data related to primarily internal processes. Spreadsheets, CSV files, and customised databases will probably more satisfactorily meet those needs.

Creating an ecosystem of open registers

Registers should replace many published lists of things as the recognised canonical sources of data wherever possible. But we won’t get there overnight. To deliver value as quickly as possible we’ll be helping to build open registers that are most commonly referenced. We’re currently working with departments and analysing the use of the open datasets on data.gov.uk to identify what these are likely to be.

The requirements that registers are ‘minimum viable datasets’, with a clear custodian and a clear purpose mean that departments and agencies will have to drive the development of much of the register ecosystem. It will also mean that data interdependencies will become more apparent. Linking between registers will make common naming conventions and standardised APIs important factors for success. Government departments working together will be necessary to achieve this and Digital Leaders, as well as the newly formed Data Leaders Network, will be central to this endeavour. The GDS Data Group will be looking to support departments in doing all these things.

Building a distributed data landscape in this way makes for a robust ecosystem which will benefit users both inside and outside government. It’s one of many steps towards a 21st century data infrastructure.

Follow Ade on Twitter, and don't forget to sign up for email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by simonfj posted on

Sorry. "If we Don't introduce a Global sharing culture..."

Comment by simonfj posted on

Thanks Ade,

That makes it much clearer about what you are doing with registers.

You must apologise to Paul for me as my correspondents and I, misunderstood your focus. We had the impression that you would be addressing registers from the users perspective and not the central gov's departmental perspective. (No sleight intended)

As you know, the peculiar nature of the UK electoral system is that voters' authoritative Register is kept at a local gov's ERO. As this service is the foundation of the way many other user services are built, "and we learn from doing" (and we want to see you get runs on the board quickly and easily), can I just think this one though aloud.

We have the IER service, which if it had an api, would enable almost-instantaneous matching of an applicant's NI number to a DOB and pass it to the relevant ERO via a hub/attribute exchange. (Perhaps that is done by now). https://technology.blog.gov.uk/2014/07/10/under-the-hood-of-ier/

The main consideration here is that ERO's act as the best authority for a person's address. But when a mover registers to vote this attribute is not passed up to the exchange so that central departments can be informed (told once) of a change in address. This would be quite an attractive service which may encourage more people to register to vote.

It also follows the principle that every register (relating to a user) retains only minimum attributes.

This user-centric approach does have other implications in the development of information databases, but in the exchange of attributes of the users, which will provide their credentials to build and access open, shared, and private (federated) registers. Anyhow. Just a thought.

Would you also give this some thought as your biggest challenge is, as you say, trying to get the departments to collaborate. It seems a little easier in Aus as Paul Shetler was able to come in, with the knowledge of what happens by taking the great leap to bringing their publications under one masthead. Innovation will always put a few noses out of joint.

Rather than expecting our department heads, can we help them by developing a social network between specialists/peers in different countries, and start including the local govs. That happens in the eduspace. The khub in the UK is one start. If we are going to introduce a Global "sharing" culture, rather than one where everyone (Nationally and Locally) "delivers", all we are going to is end up with are National registers that can't serve a WWW audience. And that where the real Innovation starts. Enough. Good luck to you and team.